The Iron Triangle – A great tool for successful Procurement and Contract Management

February 15, 2014

How do you distinguish if you pay too much? What are the elements you need to have in mind when putting together a deal?

There may be a lot of books and literature that describes this point. Nothing I have found though, makes this clearer than the concept of the Iron Triangle.

The Iron Triangle was part of a presentation by Sara Cullen at an IACCM workshop in Melbourne last year (you can find this concept in her book Outsourcing: All you need to know).

After hearing about this concept, I found that I was using it in discussions with colleagues more and more and that it was very useful to clarify situations and issues.

So, I thought I’d share it with you along with some tips on how to avoid been caught in what is called the “Winner’s Curse”.

THE EXAMPLE

Sara, in her book, mentions the example of a retailer’s IT department (the Customer) who chose to go to tender for the data centre operations placing big emphasis on the price, on the belief that the services and the providers themselves were undifferentiated. So, the lowest bid (30% below the second lowest) won the tender. Value for money was not assessed or thought it was of importance.

Very quickly in the deal though, scope and price variations became the norm. KPIs were not achieved as these had been set up as targets and not as minimum standards and the Customer had not dedicated time to develop an SLA that was customised to the Customer’s needs.

Additionally, the Customer had now to dedicate a full resource to variation management. Demand peaks had not been accounted for within the tender price and so, even more resources had to be acquired. The story goes on.

So, as you can appreciate the total cost of this contract was very high. Actually, Sara reports that it was higher than the highest bid and the Customer was constantly preoccupied with fighting fires rather than adding value.

This a typical case of what is called the Winner’s Curse.

THE IRON TRIANGLE AND THE WINNER’S CURSE

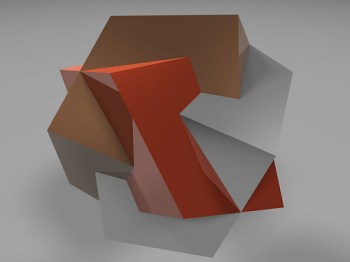

To better understand what happened, we have to look at the concept of the Iron Triangle (picture above).

The Iron Triangle reflects the basic three elements of a successful deal. These are:

- Scope – what the products / services are.

- Performance (Quality) – what standards are required for the products / services

- Price – what price will be paid for the products / services

Focusing on the Price levels for now, this concept depicts three different price levels with the analogous levels of Scope and Performance (Quality).

1. The Winner’s Curse – This is the price a bidder will bid in order to win a tender. (P1)

2. Price to do – This is the price required to do the job including a reasonable margin (P2)

3. Price to act in Customer’s favor – The highest bid of all which corresponds to the highest quality and scope (considered in Customer’s favor) (P3).

In the above example, what the IT department (the Customer) failed to understand is, that selecting the vendors based on the P1 price level (the Winner’s Curse) means that the Provider needed to cut corners to recover its cost and potentially make a margin.

On the other hand, the expectation the Customer has in terms of Performance (Quality) and Scope usually resembles the corners of the Triangle corresponding to price level P3.

This means that the eventual triangle the Customer would require consists of the highest Quality and Scope levels but the lowest price. This results in a skewed triangle and is unsustainable.

Hence, what ensued the deal in the above example was the breakdown of the relationship and the spiraling of costs.

So, reflecting on the Iron Triangle, sourcing should be a search for the best value for money deal, taking into account the Scope, the Performance and the Price from the start.

TIPS TO AVOID BEEN CAUGHT IN THE WINNER’S CURSE

So, what are some tips to avoid been caught in the Winner’s Curse?

- Be informed about what you want (specifications), how you want it delivered (quality), what value-additions are required (if any).

- Be in the know, from a Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) perspective e.g. estimate the transition costs for changing suppliers (should you want to add them in the mix) etc

- A deal made must include clarity around these three items Scope, Quality and Price. Be sure to cover all of those from the start.

- Have a variation process agreed.

- Have an exit strategy should things go wrong.

- Know the triangle you are in at every deal and prepare for any shortcomings if in fact you are forced to go for a winner’s curse.

Do you know what triangle you were part of the last time you did a deal?

Image courtesy of Sara Cullen / www.whiteplumepublishing.com